We use cookies to make your experience better. To comply with the new e-Privacy directive, we need to ask for your consent to set the cookies. Learn more.

I Was Supposed to Go to WVU

Nearly thirty years ago, in the 1992-93 school year, I was one of the top rifle recruits in the country. Everyone thought I was going to go to West Virginia University (WVU), with good reason. They had won the previous five NCAA Rifle Championships, were well funded, had good range facilities, could offer me a scholarship, and had the best rifle coach in collegiate athletics in Marsha Beasley. By going there I could reasonably expect to help the team win three or four more NCAA titles. It was a natural fit; I should go to WVU.

But the thing is, what’s the joy of sport, if you know you’re going to win?

I decided against WVU early in my college search almost because they were so good. I wanted to go somewhere where I might contribute to their emergence as a NCAA contender. I decided instead to focus my search on finding a school where I could train and that offered an excellent engineering school.

The academies offered great opportunities. Army and Navy both fit the bill, but I didn’t want to join the military in an era when I wasn’t welcomed. I had phone calls from Rutgers and OSU, but they just didn’t seem right for me. Then one day, Harry Mullins from Kentucky called.

I honestly don't remember much about that first phone call, other than that Harry was obviously eager. He talked while I listened trying to figure out what this Kentucky school was. But they had a rifle program, a hopeful coach, and a good engineering school.

My recruiting visit was awkward. Everyone on the rifle team kept trying to compare me to Jamal Mashburn, and I had no idea who he was. I found out later he was credited with resurrecting Kentucky basketball after a suspension. Fun fact, I literally didn’t know Kentucky had a basketball team, let alone the winningest program in NCAA basketball history. Then, there was the chemistry class I attended with one of the team members. I got in trouble with the professor when she gave the class a pop quiz and I didn’t take it with them.

Regardless, in the end, I chose to study at the University of Kentucky.

It’s hard to explain just how lacking the Kentucky rifle program was at the time. They had no scholarships, an inexperienced part time coach, a backstop that only rose 4 feet (you couldn’t even hang standing targets at the correct height), and no travel budget to speak of. The Athletic Director, C. M. Newton refused to spend money on the team until it started winning. Kentucky had never qualified for the NCAA Rifle Championship as a team; they only ever qualified individuals, and not many of them.

The team coach, Harry Mullins, hardly knew what to do with me when I landed on campus. I had to skip freshman orientation, and flew in on a red-eye the day before class, as I was competing in the USA Shooting national championships. He had his friend, a policeman, pick me up at the airport in his squad car. The next day I attended my first class, Calculus 3. By the weekend I was already training, but only after Harry made a key for me so I could physically get into the range.

Then there was my ammo bill; Harry couldn’t afford it. I literally dry fired a third of my time just to save on costs.

When the season started in September, the rest of the team started to train with me on the range. Jamie Ponton was the only senior; she was the leader of the team. We had two good sophomores that Harry recruited the year before, Mike Singer and Nancy Johnson, and two Freshman recruits who started with me, Owen Blakemore and Mike Boggs. This plus a rag-tag group of walk ons, including a couple that had never shot competitively before setting foot on Kentucky’s campus. Few of them were aware of the training required to reach the NCAA Championship. I tried to lead by example, being the first one on the range, and the last one off.

Our season began with a shoulder to shoulder match at Murray State. I won the air rifle event and finished second in smallbore. The team finished down on the list. But at that match something started to change in our team. They saw a connection between my training and my scores. By the next week there was a noticeable uptick in training hours logged on the range. The team started training more, getting better as they did.

The story of my freshman year could not be told without telling the story of Mike Boggs. He was a freshman teammate from Shelby County, Kentucky who grew up dreaming of playing Kentucky basketball. Thankfully he became a member of the Kentucky Rifle Team instead. At the start of the season he really wasn’t shooting well at all, averaging mid 1000s smallbore at (in the 1990s the smallbore course of fire was a 3x40), and barely even making the second team. We became friends, attended chemistry together, and had lunch before practice.

One day he asked me to help him with his kneeling. “Sure,” I said. We worked together to rebuild his position. I don’t remember doing anything revolutionary, but from that day forward he treated me like an oracle. His kneeling scores went up 40 points overnight, as did his confidence. Boggs began to join me on the range every day for training, we shared training insights, and most importantly he worked his butt off.

In four-person team matches, it is rarely the best shooter that wins championships. It's almost always the number four team member who makes the difference. By the end of our freshman season, Boggs’ scores were peaking. Coach Harry took a gamble and put him on the team as our fourth athlete. Spoiler alert: the gamble paid off.

That Spring we shocked the college shooting world by qualifying for the NCAA Championships. This was the first time ever for Kentucky. We were thrilled to be invited, but what followed was even more improbable.

The NCAA Championships that year were held at Murray State University, in Murray, KY. In what has since become a Kentucky Rifle Team tradition, we went bowling after eating at the finest restaurant in town, the Sirloin Stockade, an all-you-can-eat buffet with a giant cow in the parking lot. It's a culinary travesty that they never earned a Michelin star.

At the championship, our teammate Nancy Johnson won the individual air rifle title. I finished fourth smallbore. Then on team day, we won the air rifle team title, and finished third overall—this was Kentucky’s first NCAA Rifle podium position. Harry Mullins deservingly was recognized as the coach of the year.

Everyone was asking, how did this no-nothing team from a year ago rise up and finish third? How did we beat the likes of Murray State, Navy, Xavier, all established teams with far better budgets and recruiting? How did we beat WVU in air rifle? Were we a “Cinderella team” or would Kentucky return next year?

A special moment came after we were all done shooting at the end of the Championship. The WVU team came up to us and gave us sincere and heartfelt congratulations. I’ve always remembered their display of sportsmanship.

To prospective NCAA recruits who are reading this essay, there are plenty of good reasons to sign with one of the top programs of the country: WVU, TCU, Alaska, and my alma mater Kentucky. They are all good choices, and there are many other fine schools right behind them as well. Choose a school that is right for you. If you are like me however, think past these elite programs and relish in the opportunity to really make a difference somewhere new.

The safe and easy path was not for me. I turned down WVU because they were so dominant. I chose to go to Kentucky because that gave me a chance to contribute to the emergence of a new program. My selection, and the Kentucky Rifle Team’s successes in that breakthrough year, led to two pivotal paths for the sport.

First, to his credit, C. M. Newton, the UK Athletic Director, started to fund the rifle program, paid to install a new rifle range backstop, gave Harry Mullins a full time position, and provided Rifle Team scholarships. Kentucky was not a “Cinderella,” as Kentucky earned podium finishes each of my four years, and continued to earn many more after my graduation. Fast forward to today, Kentucky is now one of the USA’s elite college rifle teams. They have won four National Championships, produced multiple Olympians, and are considered one of the favorites again this season. They are well-funded, have good facilities, and excellent coaching.

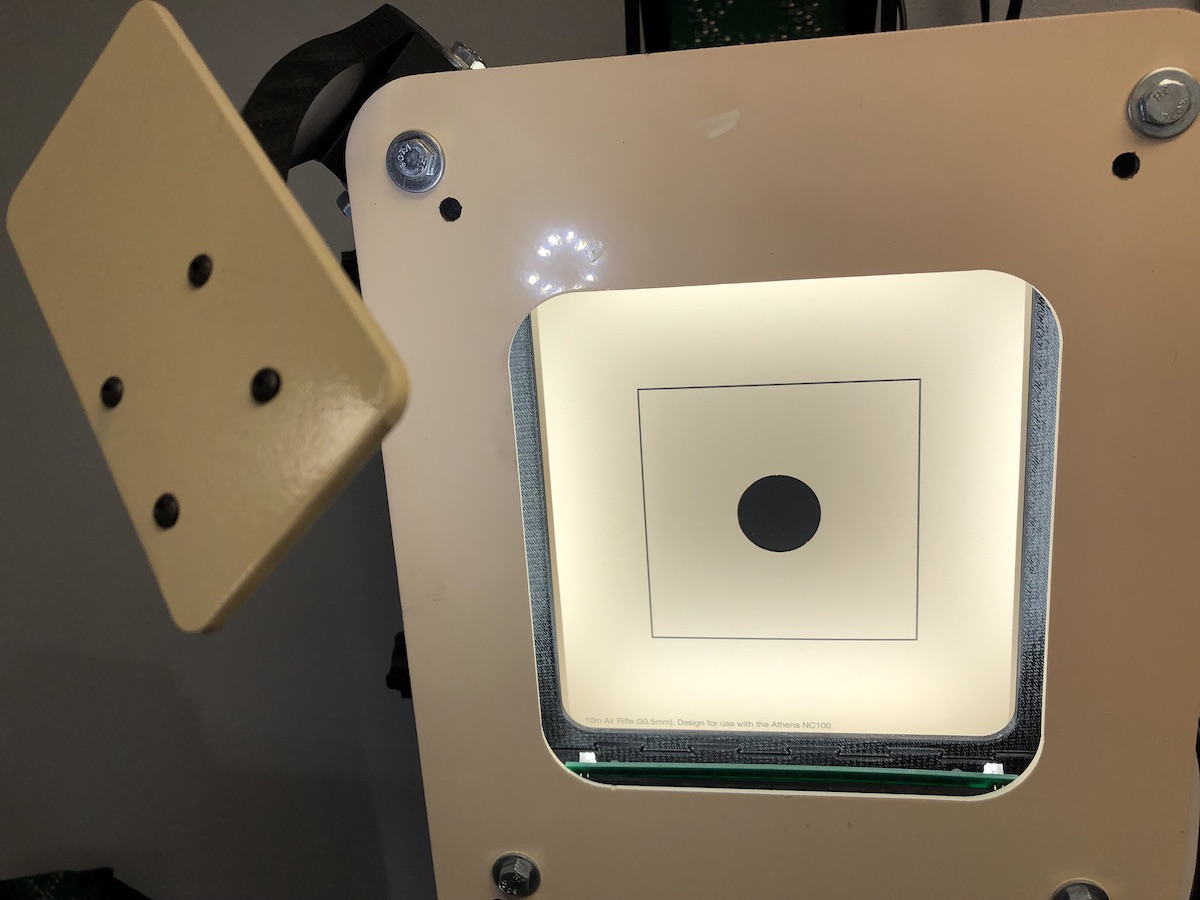

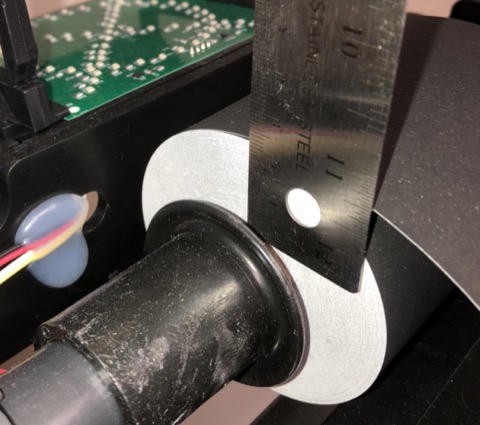

Second, I graduated from Kentucky magna cum laude with a degree in computer science. Continuing my academic career, I went on to study at Kansas University to earn my Ph.D. in electrical engineering. There I met John Gauch, a computer vision professor, in whose class I wrote the early algorithm that is now the foundation for Orion and Athena. I did my post graduate studies at the University of Southern California, studying field programmable gate arrays. This led me to the breakthrough idea of the reconfigurable rulebook, the technological backbone that accommodates the diversity of the sport of Shooting and now powers Scopos’ software.

I was supposed to go to WVU. Instead, this skinny, gay, nerdy, athlete decided to attend a then unfamiliar team named Kentucky, and ended up being privileged to be a key player in the birth of one of today’s leading college rifle programs.